The Medical Film Symposium will examine—through screenings, presentations and papers—the relationship between moving images and medical science. Medical films comprised one of the earliest film genres, but the vast majority of these films are unseen and unknown today...

I can hardly wait for the upcoming Medical Film Symposium, taking place later this month in Philadelphia, PA--January 20-23 to be exact. As far as I know, this ambitious event--featuring over a dozen academics, film-makers and film-historians screening and expounding on films that explore "the relationship between moving images and medical science"--is the first of its kind, and promises to be a really fascinating, compelling, and, at times, perhaps even disturbing event.

As if the stellar line-up (see below) and opportunity to see obscure, under-seen old medical films weren't enough of a draw, the spaces housing the symposium are nearly as alluring as the events themselves; the incomparable

Mütter Museum (!!!) will be hosting Saturday's day long program, and Friday night's screening will take place within (yes, within!) the Pennsylvania Hospital

Surgical Theatre, the oldest surgical theatre in the United States. As an added bonus, attendees of this screening will have the opportunity to take in the Jan van Rymsdyk pastel drawings on view at the Pennsylvania Hospital's medical library--as mentioned in

this previous post--before and after the event.

Other highlights of the symposium include Saturday night's "Medical Film Cabinet of Curiosities" co-curated by

the Secret Cinema and

North Carolina's A/V Geeks, and friend-of-Morbid-Anatomy

Michael Sappol's presentation "Difficult Subjects," in which he will screen some harrowing medical film clips from the collection of The National Library of Medicine and "think aloud about the cultural meaning, scientific uses, ethical issues that arose in the making and showing of such films in their first historical moment" as well as today.

Full conference text follows; its a bit wordy, but well worth reading. The deadline for registration is this Friday, the 15th of January; the conference cost is only $80 ($50 for students), which includes admission to all events, plus breakfast and lunch on Saturday. I will definitely be there, in my role as "official blogger" for the event, and hope to see you there, too. This looks seriously not-to-be-missed, and lets hope it is the first of many such events exploring seriously the interstices of art and medicine, death and culture.

Medical Film Symposium, January 20-23, 2010

Wednesday, January 20

7:00pm

Screening of A Man to Remember at International House

(presented by Nico de Klerk of the Nederlands Filmmuseum) [info]

Preceded by opening of Radiologic Images exhibit (begins at 6:00pm)

Thursday, January 21

7:00pm

Film screening at International House

(curated by Barbara Hammer) [info]

Friday, January 22

7:00pm: Film screening within the historic Pennsylvania Hospital Operating Theatre

(curated by Andrew Lampert and Greg Pierce, open to symposium attendees only)

Saturday, January 23

9:00am to 5:00pm

A full day of presentations at the Mütter Museum

(Philadelphia College of Physicians )

- "The Body Visible"

R. Nick Bryan, University of Pennsylvania

While mankind has always been driven by morbid curiosity to see inside its own body, medical practitioners have had a more urgent need to do so – their business lies there-in. The spatial complexity of the body demands imaging not only for diagnosis but for successful treatment. However, the unaided human visual system that depends on visible light cannot see below the skin. Prior to Rontgen’s discovery of x-rays in 1895, the interior of the body could be imaged only by cutting through the skin and ‘letting the light in.’ Unfortunately, until the late 19th Century, such invasive medical imaging was usually performed after or immediately prior to death. Despite an initially slow and crude start with ‘Rontgenography’, the eternal goal of real time, safe, non-invasive, detailed imaging of the living human body has come to dramatic fruition in the past decade. With modern CT, nuclear, MR and ultrasound scanners, vivid static as well as moving images of all major organ systems are now routinely performed, as will be illustrated by videos of, “My Body”, a self-exposé by the presenter.

- "Between Photography and Film: Early Uses of Medical Cinematography"

Scott Curtis, Northwestern University

From the beginning, medical researchers and physicians eagerly appropriated the new technology of motion pictures. For some, especially those interested in a more "scientific" approach to medicine, film represented an improvement upon and transformation of serial photography--that is, they regarded motion pictures as a series of still images. Others extended medical photography's more common use as documentary evidence to their application of cinema. Still others emphasized the spectacular and moving quality of the cinematic image in their promotion of film as an educational tool, often distinguishing it from photography. This presentation, then, will survey the professional perceptions and uses of medical cinematography in its first two decades and compare those uses to the functions, genres, and venues of nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century medical photography.

- "The Flow of Life: Moving Images of Magnified Blood"

Oliver Gaycken, Temple University

A staple of medical moving-image presentations was the spectacle of blood as seen under a microscope projected onto a screen. This talk will consider some examples of this tradition that range from nineteenth-century lantern lectures to reminiscences of researchers to the incorporation of this genre into the medical motion picture.

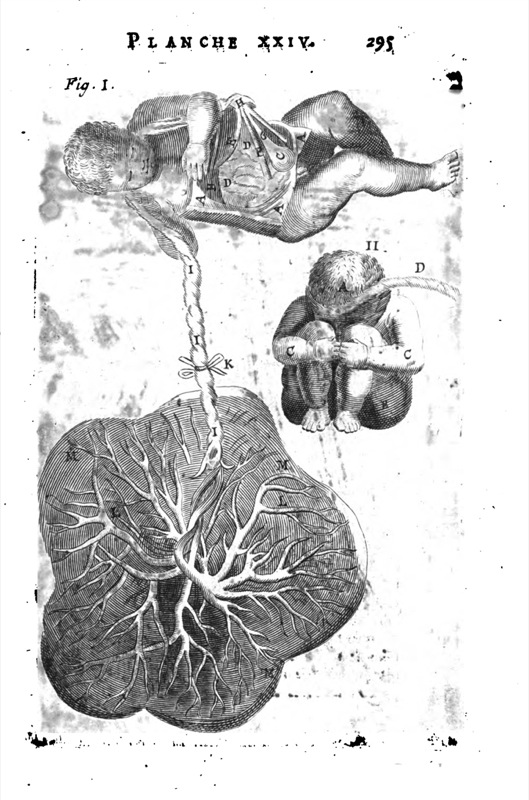

- "Complexities and Enigmas of Cinefluorography in the work of Dr. James Sibley Watson and Colleagues"

Barbara Hammer (Independent filmmaker) and Patti Doyen (George Eastman House

This presentation will explore through Watson et. al.'s text and images the discoveries and problems of the Rochester medical team that led to mechanical inventions that enabled views of the interior of the human body. The uses and abuses of the techniques will be highlighted as well as the artistic curiosities Watson pursued in spectacles that had no scientific purpose.

- "Telephone Operator, Camera-Operator: Laryngoscopy and High Speed Motion Pictures at Bell Labs"

Mara Mills, University of Pennsylvania

During the early twentieth century, telephone engineers became authorities on psychoacoustics and otolaryngology. In the interests of visualizing speech production and the movement of circuit components, they also made key contributions to high speed motion picture photography. This talk will survey the history of laryngoscopy through the 1940s, concluding with a few remarks about the nature of the "telephonic gaze."

- "Edgar Ulmer and the National Tuberculosis Association: Fighting Faith in the War Against TB"

Devin Orgeron, North Carolina State University

From the late 1930s through the early 1940s, well-known “B” movie director Edgar Ulmer (sometimes called the King of PRC) directed eight health shorts for the National Tuberculosis Association. A strain of fatal contamination runs though all of Ulmer’s work and is brilliantly, if oddly articulated in these tuberculosis films, many of which are aimed at specific American racial minorities and the inadequacies of their sometimes imported faith in the face of the disease. Along with their fit within Ulmer’s career, I hope to illustrate the role these films played in shaping 1930s/1940s notions of race, religion, and disease.

- “‘Spectacular Problems in Surgery’: Medical Motion Pictures at the American College of Surgeons”

Kirsten Ostherr, Rice University

Early in the twentieth century, the American College of Surgeons was a leading national force in the use of motion pictures for educational purposes. This movement encompassed all facets of the motion picture industry (ranging from education to entertainment), and established the ACS as a central institution in the history of cinema. Moreover, the ACS became an important vehicle for international medical education through motion pictures after World War II, and this aspect of ACS activities provides an important and unique perspective on the varied global uses of medical media in the postwar era. This presentation will address the medical motion pictures produced, reviewed, distributed, and exhibited by the ACS, from the late 1920s to the present. The talk will be based on research at the American College of Surgeons archive, which contains paper records related to a vast range of medical motion pictures. These films were primarily technical medical films produced by specialists for other specialists, as well as for medical student and resident training. Since the ACS films were concerned not only with medical education but also with the public image of the medical profession, this history serves a critical function in assessing the role of visual images in shaping the popular and specialist cultures of medicine throughout the twentieth century.

- "Difficult Subjects: Working with Films from the Collection of the National Library of Medicine"

Michael Sappol, History of Medicine Division at the National Library of Medicine

Historical medical film is notable for its representation and documentation of "difficult subjects"—the interior of the body, death, disgfigurement, radical medical intervention, infliction of pain on patients and research subjects, behavioral disturbance, venereal disease, emotional and physical distress, etc. Although publicly available, such films are rarely screened and, as a result, rarely studied. This presentation will screen a selection of these difficult films, explore their unique history, uses and abuses, effects on viewers, and the larger issues that they raise.

- “Research, education, and patient care: archival medical film collections at academic health institutions”

Timothy Wisniewski, Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives, Johns Hopkins University

This presentation will focus on the institutional context of archival film collections produced within academic health centers, using the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions as the primary example. The presentation will look at historical examples of centralized and decentralized models of film production at Johns Hopkins, and compare genres of medical film as produced for educational, clinical, or biomedical research purposes. Finally, the presentation will discuss the value of making these often unprocessed or restricted collections accessible for research and use by diverse groups of users.

Saturday, January 23

8:00 pm

A MEDICAL FILM CABINET OF CURIOSITIES

Film screening at Moore College of Art (curated by Skip Elsheimer & Jay Schwartz)

Admission: $7.00 [admission included with symposium registration]

Co-programmed by Jay Schwartz of the Secret Cinema and Skip Elsheimer of North Carolina's A/V Geeks, who will be present at the screening. This will be Skip's first return visit since he presented his popular program S IS FOR SISSY! at Moore, just over one year ago.

The program will include:

- FEET AND POSTURE (1920s) - This reel, from the earliest era of 16mm educational films, aims to explain the physiology of feet and how to best take care of them. It demonstrates through x-rays how the well-dressed young flapper of the time often did not choose the best footwear. Made with the cooperation of M.I.T. and the American Posture League.

- CELL WARS (1987) A lively introduction to immunology that shows kids how the body´s cells defend themselves against invading germs. Crazy-costumed actors and dazzling video effects demonstrate what happens after germs enter the body through a skinned knee.

- CRYOEXTRACTION (195?) - A sales and demonstration film showing off the Thomas Cryopter--a device which resembles a power router, which is then shown in use for eye surgery.

- COLDS AND FLU (1975) - Kids dressed in armor battle each other to seize control of a giant-mouthed castle.

- ACHIEVING SEXUAL MATURITY (1973) - At a time when DEEP THROAT played in neighborhood cinemas alongside traditional Hollywood fare, educators struggled as to how to best meet increasingly rebellious high school and college students on their own terms. It was during this possibly unique moment in pop culture that ACHIEVING SEXUAL MATURITY was successfully sold to school districts around the country. Its use of graphic live photography of nude males and females to explain and illustrate sexual anatomy from conception to adulthood is today quite surprising.

- NON-SYPHILITIC VENEREAL DISEASE (195?) - This short film made for the medical community--in still-stunning Kodachrome color -- details a variety of exotic venereal diseases, in close-up after horrifying close-up. This mainstay of Secret Cinema Halloween screenings is guaranteed to have audiences screaming in terror.

- JUST AWFUL (1972) This film was made to help eradicate any fears children may have about visiting the school nurse.

SECRET CINEMA WEBSITE: http://www.thesecretcinema.com

For more information about the symposium, visit the conference website by clicking

here; you can find out more about registration

here. For more about symposium hosts the Mütter Museum and Pennsylvania Hospital Surgical Theatre, click

here and

here, respectively. Please feel free to contact me with any questions by clicking

here.

Hope to see you there!

Images: From top: Still from SANCTUS, dir. Barbara Hammer, Courtesy of Barbara Hammer; X-rays by Dr. James Sibley Watson, Courtesy of Barbara Hammer; Maurice L. Blatt, Samuel J. Hoffman, & Maurice Schneider, “Rabies: Report of Twelve Cases, with a Discussion of Prophylaxis,” Journal of the American Medical Association 111 (1938): 688-91